Introduction

For the last five years, there have virtually been almost no global-scale application-layer attacks.

During this period, the industry has learned how to cope with the high bandwidth network layer attacks, including amplification-based ones. It does not mean that botnets are now harmless.

End of June 2021, Qrator Labs started to see signs of a new assaulting force on the Internet – a botnet of a new kind. That is a joint research we conducted together with Yandex to elaborate on the specifics of the DDoS attacks enabler emerging in almost real-time.

Discovery

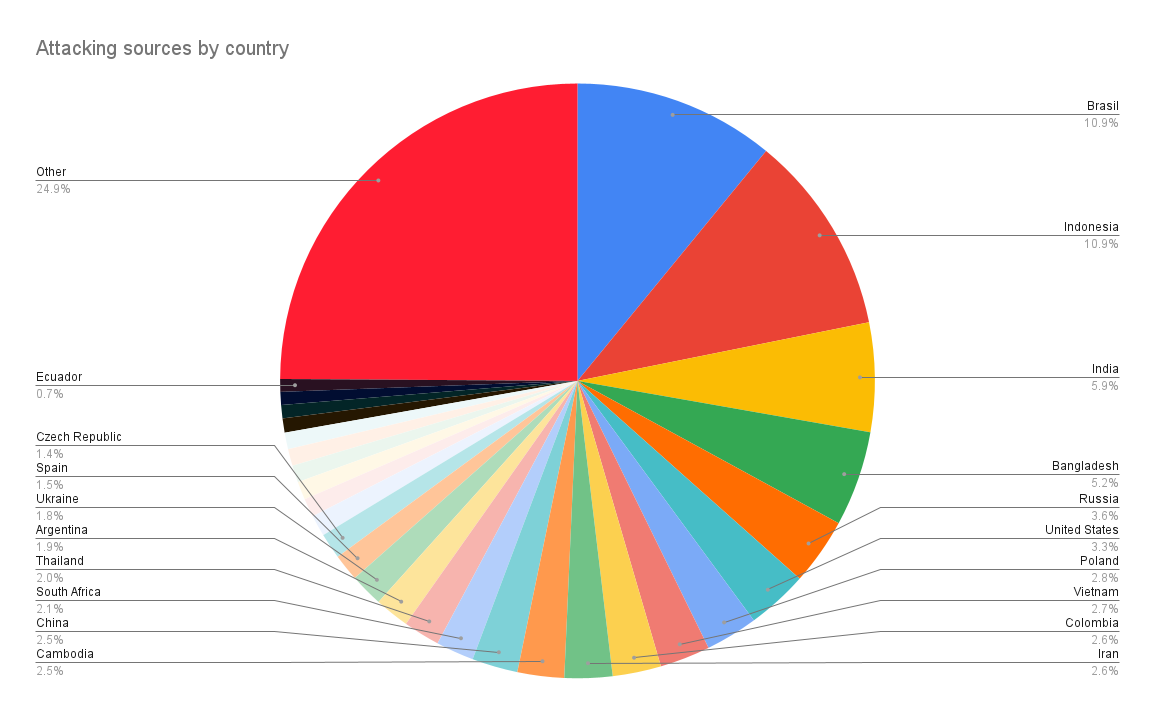

We see here a pretty substantial attacking force – dozens of thousands of host devices, growing. Separately, Qrator Labs saw the 30 000 host devices in actual numbers through several attacks, and Yandex collected the data about 56 000 attacking hosts.

However, we suppose the number to be higher – probably more than 200 000 devices, due to the rotation and absence of will to show the "full force" attacking at once. Moreover, all those being highly capable devices, not your typical IoT blinker connected to WiFi – here we speak of a botnet consisting of, with the highest probability, devices connected through the Ethernet connection – network devices, primarily.

Some people and organizations already called the botnet "a return of Mirai", which we do not think to be accurate. Mirai possessed a higher number of compromised devices united under C2C, and it attacked mainly with volumetric traffic.

We have not seen the malicious code, and we are not ready to tell yet if it is somehow related to the Mirai family or not. We tend to think that it is not, since the devices it unites under one umbrella seems to be related to only one manufacturer – Mikrotik.

Another reason we wanted to name this particular botnet, operating under elusive C2C, with a different name – Mēris, which means "Plague" in the Latvian language. It seems appropriate and relatively close to Mirai in terms of pronunciation.

Specific features of Mēris botnet:

-

Socks4 proxy at the affected device (unconfirmed, although Mikrotik devices use socks4)

-

Use of HTTP pipelining (http/1.1) technique for DDoS attacks (confirmed)

-

Making the DDoS attacks themselves RPS-based (confirmed)

-

Open port 5678 (confirmed)

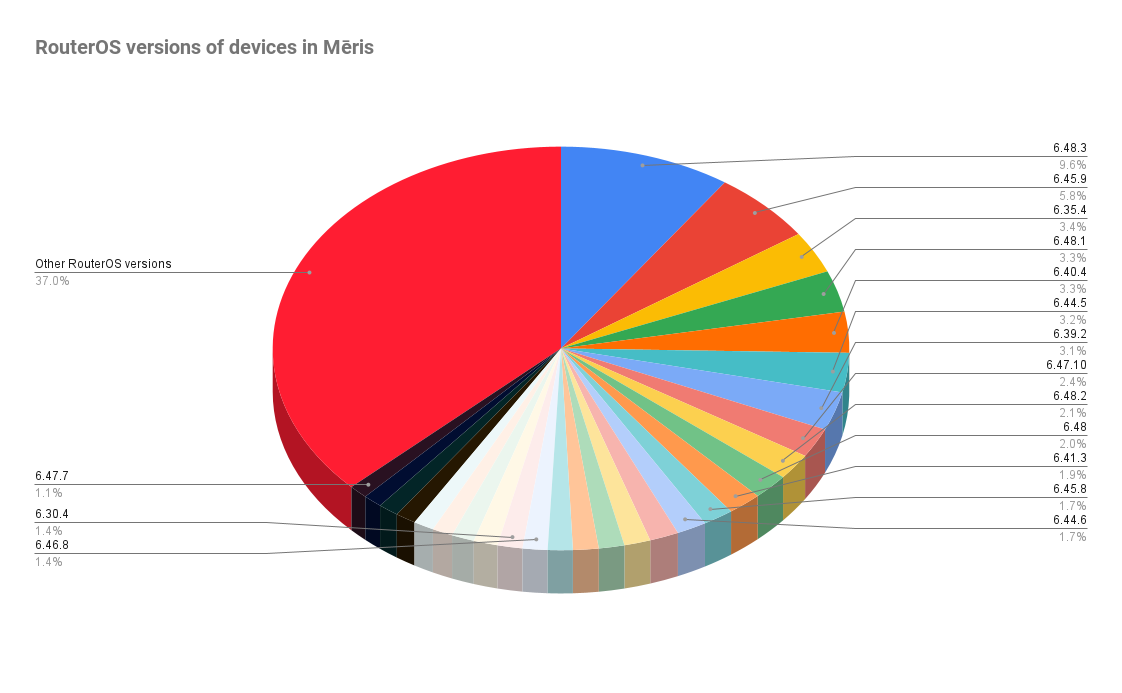

We do not know precisely what particular vulnerabilities lead to the situation where Mikrotik devices are being compromised on such a large scale. Several records at the Mikrotik forum indicate that its customers experienced hacking attempts on older versions of RouterOS, particularly 6.40.1 from 2017. If this is correct and we see that old vulnerability still being active on thousands of devices being unpatched and unupgraded, this is horrible news. However, our data with Yandex indicates that this is not true – because the spectrum of RouterOS versions we see across this botnet varies from years old to recent. The largest share belongs to the version of firmware previous to the current Stable one.

It is also clear that this particular botnet is still growing. There is a suggestion that the botnet could grow in force through password brute-forcing, although we tend to neglect that as a slight possibility. That looks like some vulnerability that was either kept secret before the massive campaign's start or sold on the black market.

It is not our job to investigate the origins, so we must move on with our observations.

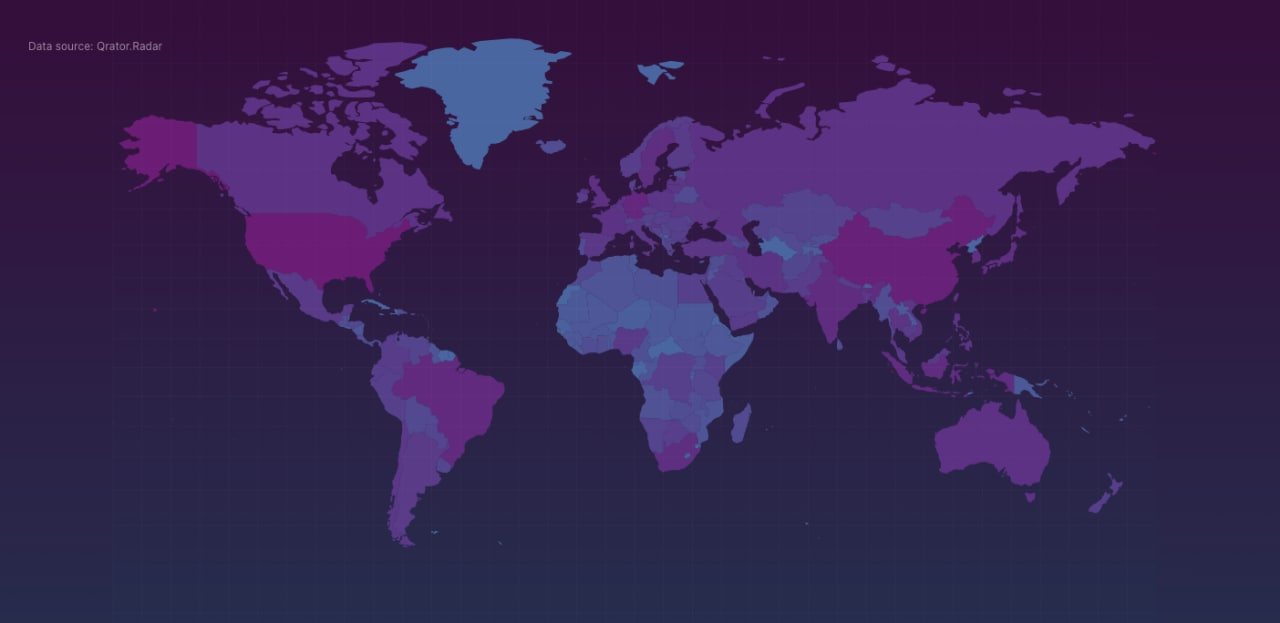

In the last couple of weeks, we have seen devastating attacks towards New Zealand, United States and Russia, which we all attribute to this botnet species. Now it can overwhelm almost any infrastructure, including some highly robust networks. All this is due to the enormous RPS power that it brings along.

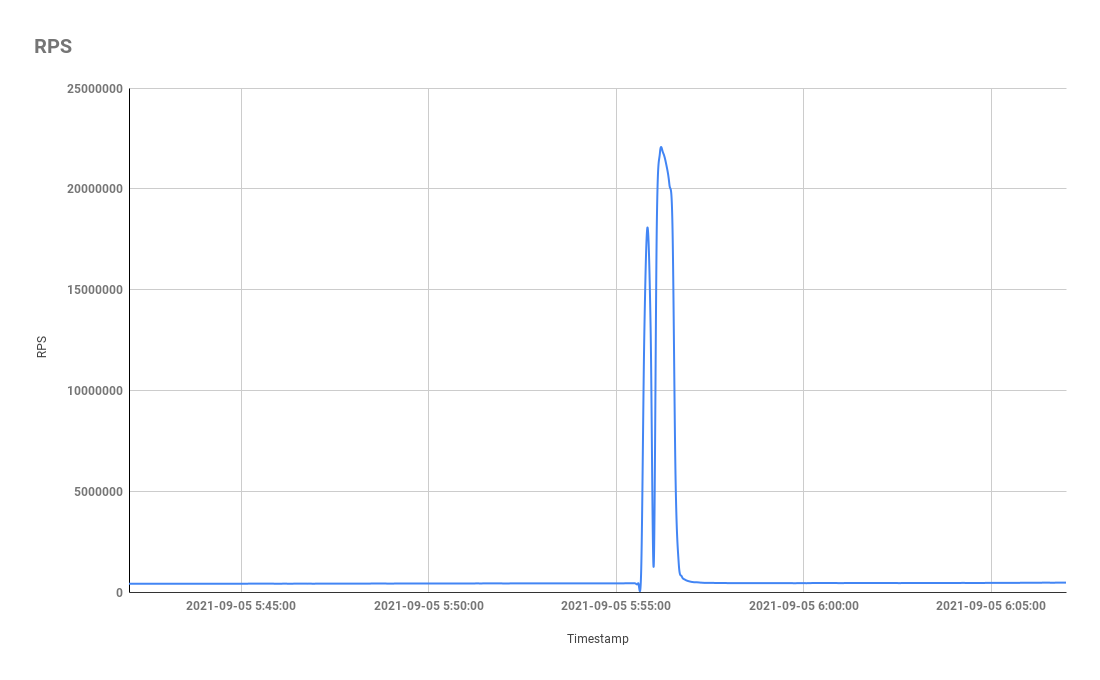

It's been in the news lately about "largest DDoS attack on Russian internet and Yandex", but we at Yandex saw a picture much bigger than that. Cloudflare recorded the first attacks of this type. Their blog post of August 19, 2021, mentioned the attack reaching 17M requests per second. We observed similar durations and distributions across countries and reported this information to Cloudflare.

Here is the history of attacks from the same botnet we recorded at Yandex:

-

2021-08-07 - 5.2 M rps

-

2021-08-09 - 6.5 M rps

-

2021-08-29 - 9.6 M rps

-

2021-08-31 - 10.9 M rps

-

2021-09-05 - 21.8 M rps

Yandex' security team members managed to establish a clear view of the botnet's internal structure. L2TP tunnels are used for internetwork communications. The number of infected devices, according to the botnet internals we’ve seen, reaches 250 000.

How exactly did Yandex withstand such an enormous amount of requests per second?

At Yandex, incoming user traffic passes through several infrastructure components, operating at different ISO/OSI layers. The first component protects Yandex from SYN flood attacks. The following layers analyze incoming traffic in real-time. Based on the technical and network statistics, the system evaluates each request for a level of suspicion. Thanks to robust and well-maintained infrastructure, we quickly scaled our components horizontally after the first attack. We were able to cope with the most significant RPS attack in Internet history without switching to an IP banning mode.

The attacking sources (IP addresses), which are not spoofed, seem to predominantly have the same trait – open ports 2000 and 5678. Of course, many vendors put their services onto those particular ports. However, the specific combination of port 2000 "Bandwidth test server" and port 5678 "Mikrotik Neighbor Discovery Protocol" makes it almost impossible to ignore. Although Mikrotik uses UDP for its standard service on port 5678, an open TCP port is detected on compromised devices. This kind of disguise might be one of the reasons devices got hacked unnoticed by their owners.

Based on this intel, we decided to probe the TCP port 5678 with the help of Qrator.Radar. The results we have gathered were surprising and frightening at the same time.

It turns out that there are 328 723 active hosts on the Internet replying to the TCP probe on port 5678. Of course, not necessarily each of those is a vulnerable Mikrotik – there is evidence that Linksys devices also use TCP service on port 5678. There may be more, but at the same time, we have to assume that this number might represent the entire active botnet.

|

Country |

Hosts |

% of global |

|

United States of America |

139930 |

42.6% |

|

China |

61994 |

18.9% |

|

Brazil |

9244 |

2.8% |

|

Indonesia |

7359 |

2.2% |

|

India |

6767 |

2.1% |

|

Hong Kong |

5225 |

1.6% |

|

Japan |

4928 |

1.5% |

|

Sweden |

4750 |

1.4% |

|

South Africa |

4729 |

1.4% |

What is important, that an open port 2000 replies to the incoming connection with a \x01\x00\x00\x00 signature, which belongs to the RouterOS protocol. So it is not some random Bandwidth test server but an identifiable one.

Citing https://github.com/samm-git/btest-opensource:

“There is no official protocol description, so everything was obtained using WireShark tool and RouterOS 6 running in the virtualbox, which was connecting to the real device.

Server always starts with "hello" (01:00:00:00) command after establishing TCP connection to port 2000. If UDP protocol is specified in the client TCP connection is still established.”

Based on our observation, 60% of attackers have socks4 open on port 5678, and 90-95% have Bandwidth Test on port 2000.

The exploit of HTTP pipelining (in HTTP 1.1, in HTTP 2.0 it is “multiplexing”) makes mitigating such attacks a task that has been long forgotten. Because, first of all, network devices usually stand for legitimate users – one could not be sure if the endpoint is entirely compromised into a “bot zombie”, or there is a part of the bandwidth used in the attack traffic, with the rest being legitimate user traffic. Users that could be registered on a resource they are trying to reach.

It means that front-end optimization could hurt even more by answering every particular network request, as the pipelining is basically about sending requests in batches to the aimed server, making him answer those trash batches of requests. Furthermore, we are speaking of HTTP requests, which already constitute the most computing power of a server, more so if we are talking about a secured connection, bearing the cryptographic load on top of usual requests.

Requests pipelining (in HTTP 1.1) is the primary source of trouble for anyone who meets that particular botnet. Although browsers do not usually use pipelining (except Pale Moon web browser, which does that), bots do that. Moreover, it is easy to recognize and mitigate since the universally accepted TCP sequence is request-response and not the request-request-request-response.

What we see here is a "quality vs quantity" scenario. Because of the request pipelining technique, attackers could squeeze much more RPS than botnets usually do. It happened because traditional mitigation measures would, of course, block the source IP. However, some requests (about 10-20) left in the buffers are processed even after the IP is blocked.

What to do in such a situation?

Blacklists are still a thing. Since those attacks are not spoofed, every victim sees the attack origin as it is. Blocking it for a while should be enough to thwart the attack and not disturb the possible end-user.

Although it is, of course, unclear how the C2C owners for the Mēris botnet would act in the future – they could be taking advantage of the compromised devices, making 100% of its capacity (both bandwidth and processor wise) into their hands.

In this case, there is no other way other than blocking every consecutive request after the first one, preventing answering the pipelined requests.

If there is no DDoS attack mitigation at the targeted server whatsoever, (not only) request pipelining could turn into a disaster, as the attacker needs much less workforce to fill the RPS threshold for the victim. And it turns out that many were not ready for such a scenario.

We have contacted Mikrotik with the data we have gathered, trying to find a solution, or notify them of our observations, minimally, which we were able to do yesterday.

Last but not least – please, keep your network devices updated with the latest firmware possible all the time. It is about each router and modem, every internet-connected device and the future of the Internet as a whole. And change your passwords. Nobody knows yet if that’s not the brute force against administration passwords – better be safe, than sorry.

UPDATE:

Mikrotik made an official statement on Mēris botnet, advising a local fix.

Also, Qrator.Radar team made an individual checker, allowing to see if a particular IP address was involved in the attacks.